Boldini, the painter of elegance

Translated by Deepl

Read the original article

In Paris, the Petit Palais is hosting the superb exhibition “Giovanni Boldini. Les plaisirs et les jours”. A treat for lovers of Belle Epoque painting, lyrical abstraction and aerial portraiture.

At the first retrospective after the artist’s death in New York, Time wrote: “He was the painter of champagne dinners and lace blouses. His art is as old-fashioned as suspenders! This assassinating statement dates from 1933, and no doubt some people would still subscribe to it today. Not so for me, nor for the tens of thousands of people who have been flocking to the Petit Palais since March to celebrate the painting of the Belle Epoque, of which Boldini is one of the most emblematic representatives.

Giovanni Boldini was born in Ferrara, Italy, on 31 December 1842, in what were then the Papal States. It was New Year’s Eve. Does this mean that he was destined to be the singer of the end of the era, the last fireworks of a brilliant period that would end in the apocalyptic apotheosis of the Great War?

The eighth child of thirteen, his father was already a painter and copyist. Little Giovanni was born with a brush in his hand and excelled in portraiture at an early age. He soon joined the prestigious Florence Academy of Fine Arts in 1862 to perfect his art, but he quickly distanced himself from academic teaching and developed his own vision of the world.

The French had already launched the Impressionist Movement, and the Italians soon followed suit with the Macchiaioli, literally the “tachists”, those who paint with spots, a derogatory nickname given to them by the critics and which they quickly began to wear as a distinctive sign of their non-conformist creativity. Boldini enthusiastically joined the Macchiaioli, a movement that was born in Florence during his studies there. Often in his life Boldini would be at the right time in the right place.

In 1867 Boldini went to the Paris International Exhibition where he made friends with Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet, Alfred Sisley, Gustave Caillebotte and Camille Corot. The range of his friendships is impressive! Later he became very close to the painter Helleu and the caricaturist Sem. In 1869 he went to London where he studied the works of Gainsborough and the English caricaturists. But he returned to Paris in 1871 and settled near the Place Pigalle. The great art dealer Adolphe Goupil signed him an exclusive contract and he was definitely launched. Year after year, his value increased as did his reputation.

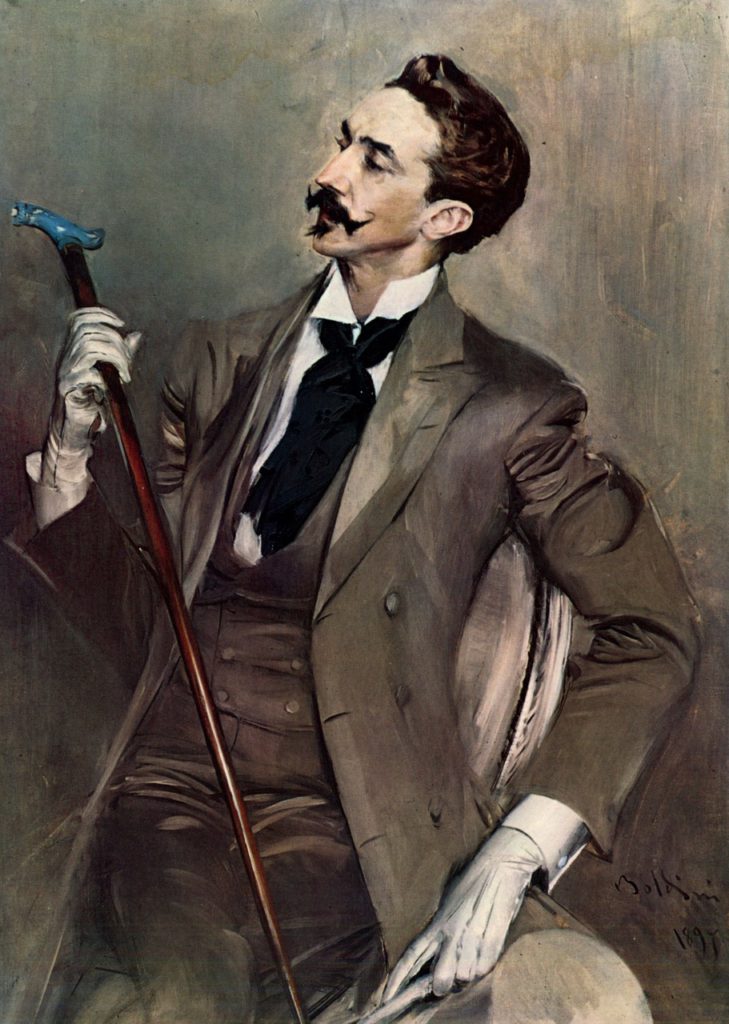

He first made a name for himself with views of the seaside, country scenes, and moments of Parisian life, very colourful, lively and charming works that can be seen at the beginning of the exhibition at the Petite Palais. But from the 1880s onwards, portraits of rich heiresses, aristocrats who set the tone for fashion, personalities and famous artists arrived. Boldini was not a cursed artist and had no desire to pull the devil by the tail; he abandoned genre painting in favour of portraits of rich clients, which were much more profitable.

Boldini painted fashionable men and women, but he went further: he made fashion. He chose the outfits to be worn by his models from their wardrobes. The creations of the great names of fashion of the time parade under his brushes: Worth, Laferrière, Poiret, Doucet, Callot. He created an archetype of the Boldinian woman with serpentine lines and airy looks, they seemed to be carried away by the wind. The critics Camille Auclair and Arsène Alexandre see in his work the expression of vanity, of the coquetry of the soul, of the neurosis of these decadent times, “everything that is not essential life”. It is precisely in this that Boldini is the true painter of his time and of modernity.

He was snapped up. America opened its arms to him, and he travelled to Germany, Spain, Morocco, Belgium, and of course his beloved Italy, to which he returned regularly. This state of grace lasts until the Great War. Then times changed, as did tastes. Boldini was no longer fashionable, but this did not stop him from continuing to paint, until his tired eyes betrayed him; he died in Paris in 1931, aged 88.

Two years earlier this old seducer had finally married a much younger journalist, Emilia Cardona. She did not mourn the great man for long; the following year she married the painter and sculptor Francis La Monaca, forty years younger than Boldini, but that is another story.

Here Boldini depicts the Venus Richelieu, a 17th century sculpture by Pierre Legros located in the royal alley in the park at Versailles. The painter returns to the place he had walked 20 years earlier, but the past splendour gives way to the melancholy of autumn. The marble reflects the reddening of the trees, while a swirl of wind, materialized by the vibrant brushstroke, lifts and turns the leaves in front of and around the statue.

Marthe-Lucile Bibesco, a historian and woman of letters of Romanian origin, met Boldini shortly before 1910. She later recalled that the ladies of the time “dressed like Boldini” and underwent weight loss treatments “to resemble the ideal woman according to the Boldinian canons of beauty”. Wearing a sumptuous, swirling black and silver evening gown, Madame Bibesco’s body is charged with flamboyant energy. However, despite the princess’s enthusiasm, the painting was refused by her husband, who considered her cleavage inappropriate.